As part of our 25th Anniversary Celebrations, we are reaching out to our members from around the country to hear about the impact AIDA has had on their amazing careers.

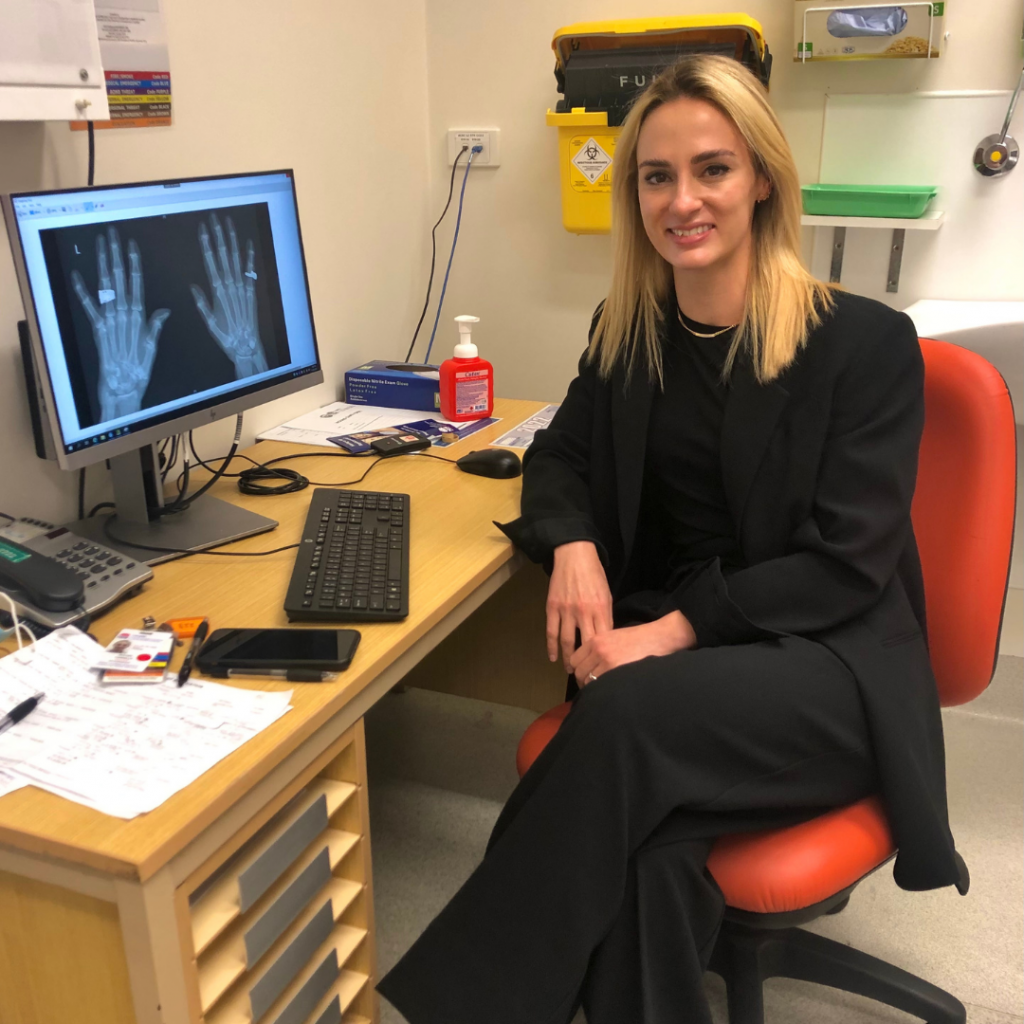

When Rachel Farrelly broke her arm when she was little, her most profound memory was being terrified of the X-ray machine. A lot has changed since then for our AIDA member, set to become the first Aboriginal female orthopaedic surgeon – and first Aboriginal female surgeon in Australia.

“I got into medicine not really having a plan of what specialty I was interested in because [orthopaedics] was such a foreign field to me. But I did it as my third clinical rotation and my attitude going into the rotation was completely turned around,” Dr Farrelly says.

Orthopaedic surgery was interesting to Dr Rachel, a Gunu woman raised on Wiradjuri country, for many reasons. Being able to restore mobility and address severe pain in her patients, from young children to seniors – was a strong drawcard for her.

“The times when you get to see a patient restored to their full mobility and go back to their normal lives, and they say thank you, that is just such a good feeling,” she says.

Women make up a small percentage in a predominantly male-dominated field of orthapaedics. However, Dr Rachel says it wasn’t difficult to find allies and mentors who supported and inspired her throughout her journey.

“I think having different mentors that you can reach out to at different time points is really crucial,” Dr Rachel says.

“I remember when I was thinking about surgery and I went to an AIDA event, Kelvin Kong was then the first Indigenous surgeon. Speaking to him about his journey made me realise that we are like all other people going through the surgical pathway and the challenges are fairly similar,” Dr Rachel says.

Dr Rachel believes having more mentors who have gone through the surgical pathway would be beneficial to young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors.

“Even if it’s not the exact field of surgery, having someone who understands the challenges and the demands of the surgical pathway and can support young Indigenous people who are keen to give it a go and try their hand in surgery is really important,” she says.

Being a surgical trainee, Dr Rachel is no stranger to challenges. She has had moments of despair where the challenges and demands of medical training became overwhelming.

“I’ve spent many a day going home, screaming at the injustice towards junior doctors or patient care, it frustrates everyone. Also having to continuously be a student as well as the expectation to be an expert is a big burden,” she says.

“I have often thought about quitting. One of the things that stopped me is the failure of a better back up plan – I can’t think of anything better I want to do!

“The other thing is sheer determination. I remember when I was thinking about studying to be a doctor, my dad, who had a big part in me starting the journey, said to me – it doesn’t matter what you do, it will take you 10-15 years of pure dedication to become an expert in any field.”

Those words of wisdom stuck with Dr Rachel, the realisation that regardless of whether you are a doctor or a farmer, everyone goes through a similar journey in their career trajectory.

“Sometimes you need a break – take a break, come back with a fresh slate and start again the next day,” she says.

Her own words of wisdom, particularly for young women interested in medicine, is to trust in your abilities.

“Particularly for young women, we are often told what we should and shouldn’t do. It’s often other people’s prejudices that they try to put on you. Don’t let it deter you. Decide what you can do and what skills you have and just go for it,” she says.

As a member of AIDA, Dr Rachel believes one of the greatest contributions AIDA makes is in representation.

“[AIDA] exists because there is a significant difference in the life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and others within our nation. We can’t expect other people to constantly keep helping us; we need to help ourselves. By putting Indigenous people within the health sector, especially as doctors and leaders within health, we can work towards equality and equity of health outcomes for our people.”

“Also, I think Indigenous kids should grow up thinking, ‘hey, I want to be a doctor when I grow up’ and I want that to be a realistic goal,” she says.

Dr Rachel believes the platform AIDA provides for empowering and supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors goes a long way in making that goal achievable.

“This is a bunch of doctors. We’re all Aboriginal, we’re all Torres Strait Islander, we represent you and where you came from and there’s people that can help you get to where you want to be in your life,” she says.

“Knowing that AIDA was there, knowing that there were Indigenous doctors that I could talk to, that could mentor me if I needed, was really helpful,” she says.